Oud to Cello: A Duet For The Ages

Interview by Jaidah-Leigh Wyatt (@wyatt_______j)

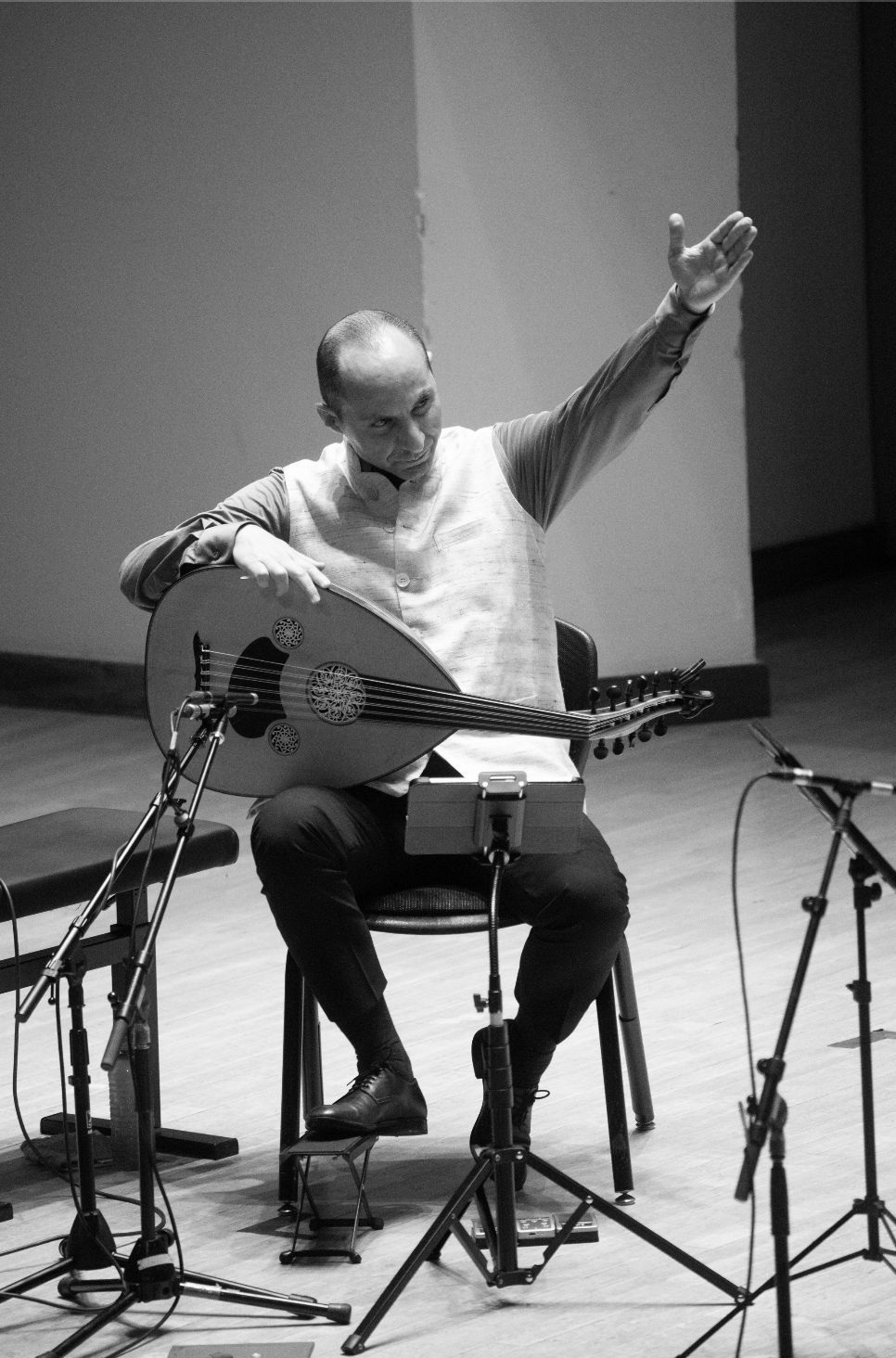

Photography by Barrett Potts aka Fifty (@fifty.jpg)

I've always found music to be one of the closest things to magic that humans can make in this world. Whether it's with instruments, voices or sounds, music creates a language that people can communicate through. It's something even animals and the natural world react to. Throughout our history, music has been adapted and expanded. Drums once made from animal skins are now synthesized through digital speakers, and a lot of music production has turned over to the electronic world - making way for new innovations of sound that weren't even a thought one hundred years ago. But that doesn't mean the instruments of the old days have been left in the dust.

Abdul-Wahab Kayyali is a visionary musician, based in Montreal. Despite only becoming a full time musician in the last three and a half years, he has undoubtedly made his impact on the world of music both internationally and locally. As a Palestinian musician, he creates music both related to his culture and expanding it - trying to find ways to combine the traditional Arabic maqam with Western polyphony. In his latest project Transposition, he paired up with Naseem Alatrash to showcase a cello and oud duet meant to challenge the notion of transposition, expose the differences and similarities in the musicality of the instruments and highlight the shared struggles they face in their communities.

I had the absolute pleasure of speaking with Abdul about this performance, and gaining his thought provoking insights on what it means to be a classical musician in the modern day, and the importance of saying something with your work:

Thank you for your time, my first question to you is just about the genre of music you play in. There are so many different genres to choose from and you gravitated towards classical music. I have a classical background as well, so I'm a huge fan, but I know for a lot of musicians they kinda tend to go towards pop music or rap or something of the sort, so what drew you to classical music specifically?

I grew up learning Middle Eastern classical music (the oud). I started studying it when I was about seven years old. When I was 14, I started studying the cello.. My background is in the world of Middle Eastern classical music but I know a little bit about Western classical music as well. I didn't study music in university. When I finished high school I studied other things, I studied political science, economics. I got advanced degrees in political science, a masters degree, a doctorate and haveworked in research.

But I kept playing. I kept playing the music that I love and the music that I love is Middle Eastern classical music. Iit was not pop, it was not commercial. There was no financial pressure on me to play music so I kinda just kept playing the music that I love to play. I eventually started composing the music that I love to compose. And then, during the pandemic I decided to go full-time.

I moved to Canada in 2020 and then a year and a half later decided to leave my research job and become a full-time musician. At that point I had already composed some pieces and I started devoting much more time to composition and arrangement and figuring out what my artistic voice is and what I want to say.

Because I studied the cello and because I love it, one of the first projects I did as a full time musician was a residency to compose and arrange my repertoire for the oud and cello duet. I started working on it honestly in late 2022.

Naseem (the cellist) was trained in jazz school but he is also very fluent in maqam, in Middle Eastern classical music. He and I had been talking about playing together, when I was still living in the US.We had made plans for a concert in April 2020 and that never materialized because of the pandemic. It’s been a dream of mine to play this music with him because I feel like technically he’s the most able to give it the kind of life that I want to hear.

It also has to due with the fact that he’s a Palestinian musician, I’m a Palestinian musician and this project is also about our identity in a kind of way and our humanity and our stories and having to live through, the genocide of our people for the last year and a half. I try to express what we’re going through in music. Most of the compositions were composed after I moved to Canada. There’s two compositions that were part of my debut album (Juthoor). One was composed by a friend and I arranged it for this combination with the cellist. There’s three compositions that I wrote for another project that I’m involved in called Les Arrivants which is like a world music trio here in Montreal. But I arranged them for this duet of instruments and then a couple of compositions that I wrote and only I wrote specifically for this project.

Thank you! I did want to ask specifically about the oud and the cello because they’re very different instruments. Other than your background with playing both instruments, were there any specifics about the instrumentation, the sound of the instruments, that made you want to have a duet between these two?

I think the cello, it’s sonority and its timbre are very specific. It’s a bowed, bass string instrument and there’s a lot of possibilities of its adaptability to Middle Eastern classical music or maqam or microtonal music in general right? The oud is plucked and it’s percussive and it’s rhythmic… The range of both instruments is the same, it goes to c2 to as high as you want. So the range is compatible. It's kind of like the same, but the timbres are contrasted.

The cello is more famous for its Western classical repertoire. Now people are starting to catch up with how versatile of an instrument it is and so you see it, it’s more used in world music, more used in jazz, more used in other genres where it typically hasn’t been associated with.

The oud is also a pretty versatile instrument and I’m not using it the way it typically has been used… like mymusic is a product of its time. It’s not old. It doesn’t seek to necessarily preserve something, it’s more of like ‘let’s develop maqam music for polyphony’ - something I’ve been interested in for a very long time. Because maqam music is not really polyphilous, it’s heterophilous. When people play, they play the same melody line but they play it in 3 different ways or 4 different ways so that they fuse their interpretation of a melodic line.

This project (Transposition) is different because clearly what I wanted to show was that the oud and the cello can have a conversation. They can finish each other’s sentences… I’ve tried playing some of these pieces on the oud solo and they don’t give me the same gratification and I imagine that the cello part on its own would not really make much sense. But the idea was ‘Okay, let's combine these instruments and let's have them say something collective’ and at the same time I think there’s a lot of beauty that can come out of something like that.

You talked about wanting to create sonic experiences and going beyond music into soundscapes. How does that creation of sound and new experiences intersect with your creation of music. Does it work in tandem or is it like these two different ideas working against each other?

Negar Bouban, an Iranian oud player, once said ‘Being a professional musician is about increasing your sensitivity to sound’ I don’t think that (music and sound) are separable. I don’t think you can make music if you’re not really sensitive to sound and sensitive to the kind of sound that you want to produce. Musicians spend their whole life chasing a sound and they spend their whole life training on an instrument technically so they can develop their own sonic identity. Some of them do, some of them don’t. But it’s the pursuit that drives them.

I want people to recognize that this isn’t just an oud this is Abdul Wahab-Kayyali on oud. I want people to recognize that I make music the way I do because I feel like I found my voice. I found my sound. I want to chase it. I want to continue developing it. This is why I practice. You practice everyday, even if you’re at the top of whatever it is that you’re at because you don’t know where it’s gonna take you.

This reminds me of another story I heard once of Pablo Casals, this really famous Spanish cellist, legendary Spanish cellist. They asked him, he was like 80 something, ‘Do you still practice?’ and he said ‘Yeah of course I still practice’ and they’re like ‘Why? Someone at your level of seniority, you’re like the best player etc.’ and he’s like ‘Well I feel like I'm getting better’ and that approach informs me too, you know? You can never own this domain. The better I become, the better I want to become. You’re chasing the sound of where the sound will take you.

The notion to keep practicing, keep striving for success and keep honing your craft displays Abdul’s humility and patience with his music. For him, there is no pinnacle or end all be all goal where learning ends and true musical mastery is reached. Music is, instead, a continuous journey, and in that sense, a constantly fulfilling one.

I feel likemusic is meant to communicate an emotional state. We all study the technique, we all spend hours perfecting the technique, and at the end of the day an audition or competition will judge you based on your execution of the technique. And that’s fine. And I respect it and I admire it and I don’t question the logic behind it. But at the end of the day music is about communicating emotion.

You either communicate the emotion or you don’t, and it almost doesn’t matter how fast you can play a scale or how great your arpeggios are, if you don’t have this expression then something is gonna be missing. If you don’t have this expressive element, if you don't connect with the audience, if you don’t make the audience feel what you feel inside, something’s gonna be lacking. Always.

And yeah you’re gonna witness a great performance, you’re gonna witness a technically flawless performance, but you’re not gonna feel anything. And that’s not what music is about to me.

To me, music is about feeling something and sharing those feelings with other people.I think is actually more elusive and difficult than being technically on top of the game because technique you can always practice technique, but developing your own sound? That’s you. It requires a level of soul searching and reflexivity and depth that not everyone is capable of and that’s what I’m chasing. I’m not chasing finger gymnastics. I don’t want people to leave a performance and say ‘You know his technique was flawless’. No, I want people to leave a performance and say ‘Wow I really felt something’.

I wanted to talk about the Transposition project. what inspired you to work specifically with Naseem and create this sort of project?

Honestly transposition, can just mean movement, travel, being unsettled, being uncomfortable, changing your environment, changing your surroundings, changing the way you think about things. Naseem is very versatile. He’s fluent in a number of different genres. And he’s comfortable being (and I don’t want this to sound cliche) he’s comfortable being uncomfortable, he’s comfortable being challenged.And ultimately I am as well. I want to learn things that I’m not very good at and I want to be put in situations where I’m forced to perform in genres of music, pitches, keys that on the oud are not very intuitive. Because I feel like not just as a musician but as a human being, when you’re taken out of your comfort zone, it really forces a moment of reckoning for you. You really have to think about who you are, what you’re about. You have to be open to learning new things. You can’t be resistant to change and resistant to adaptation, because that just makes you dogmatic and it makes you rigid and it makes you honestly, like an unpleasant person. Somebody who hangs on to something when they’re taken outside of it. Great things come out of being forced to reckon with your discomfort and this is very personal to me.

As a Palestinian-Jordanian musician, Abdul has had to reckon with his family’s history and current displacement all throughout his life, facing it while traveling, performing and doing virtually everything he does. For him, discomfort is something unavoidable, but not unconquerable. He continues to persevere in spite of his difficult relationship with his home country, proudly representing Palestinian music and culture through his work.

My family is Palestinian. We were exiled. We were thrown out of Palestine in 1948. We really had to think about what home meant. We still have to think about what home means. We still have to think about what your country means, what your identity is, what you stand for and why, you know, why did this happen to you and what you can do about it? And I feel like this really is a test, and it’s easy for people not to take this test.

It’s easy for a musician not to transpose. It’s easy for a musician not to step out of their comfort zone and just play what they're good at or what they just wanna play, but I feel like the possibilities are a lot more exciting and a lot more promising when you do step out of your comfort zone and when you do try and do things that, you know, you’re not expected to.

When the cello tries to play maqam music great things happen. When the oud tries to play tango or classical or something, that’s a pursuit that’s worthwhile. And it changes the way you do what you do originally anyway because you learn, you bring on a new skill set and you adapt it to the genre in which you’re already comfortable.

Yeah and I just think… the global situation just forces everybody to do this right now. You can’t rest on your comforts... You can’t really think ‘okay this is my comfort zone, I don’t wanna leave it.’ You’ll end up living a much poorer life as a result if you just want to draw yourself into a box and say ‘I don’t wanna get out of there’. And for me, again, for Palestinians this was never a choice. We were exiled from our homes. We had to reckon with this. We’ve had to reckon with this for the last three generations, four generations. It looks like we’re gonna reckon with it for a lot longer. But yeah, I mean… transposition really forces you to kind of think about yourself. And to think about what you’re doing. And I personally welcome these kinds of challenges and I think I grow from them as a human being and I grow from them as a musician.

I also wanted to talk about the trio you formed during the early days of the pandemic, Les Arrivants. Being isolated and settling into Montreal, a new city. You were able to come out of that with a new group of friends, finding people you have something in common with and making something new that the world hadn’t really seen before. Would you like to talk about that experience?

I moved to Montreal in the beginning of the pandemic. I knew that Montreal had a music scene, a world music scene, that I felt like would be a better fit for what I wanna do musically.

I was very lucky to be kind of integrated into the world music centre here Centre des musiciens du monde and the first thing I did artistically in Montreal was I did this residency with my two friends. Les Arrivants was a result of this residency.

The three of us were moving to Montreal almost at the same time, almost in the same kind of conditions so we really didn't have much of a background to the city and its social landscape and the only thing we could do socially was meet and play. It ended up growing into a really powerful project because one of them is a tango musician, he plays the bandoneon, and one of them is a Persian percussionist who’s just a stellar percussionist. So we all approach the project with ‘Okay what kind of thing does my tradition bring to the table? How can I make this dish tasty with my local spice?’

, I think if it wasn’t for Les Arrivants I don’t think I would’ve quit my job and become a full-time musician because Les Arrivants was getting a lot of traction very very quickly. We did the residency, almost immediately after that we did a couple of performances, we applied for a grant to do our first album, we got our first album, we recorded our first album, and then we recorded the second album. We did a bunch of residencies together, we toured together and in the two partners that I have in Ben and Hamin I have perfect partners because we have the same taste (of) what sounds good and doesn’t sound good in music and that’s actually very difficult to find because in the world of professional music everybody can play.

We share our same approach towards humanity, we come from specific places and we’re proud of our identity but we’re not overly protective of it o insular .We believe fundamentally in equality for all people and this has not been easy. Hamin comes from Iran, I come from Palestine and Jordan and Ben is Argentine-Israeli so people on the face value of it think either this is a coexistence project where we just hold hands and sing songs to feel better or that we don’t talk about the politics at all, right? And it’s neither of these things. It’s neither. I mean I think the project has taken on the life that it has taken on because we are not only colleagues we’re political allies, we believe in equality, we advocate for equality, we call out inequality in the societies that we come from and in the societies that we don’t come from right. The injustices and inequalities of the world move us in the same kind of way.

And so beautiful things can happen when you combine a tango musician, an Arabic musician and a Persian musician and just say ‘You’re equal here, you have the same responsibility, you get the same rights, you get the same privileges. Go and be a creative.’

Like this project could not exist in our home countries because one of us would be disenfranchised… based on their ethnic or religious background, and you know this kind of speaks to the equality that we’re afforded in Canada, to the promise of equal citizenship that we have in Canada and that we don’t take for granted. And that we feel empowers us and enables us to say the kind of things that we want to say artistically.

Thank you so much. And this brings me to my last question which is just simply, what is next for you on the table, musically?

You know Transposition, I’ve been working on this concert tour for almost a year now so it's really great that I’m going to get to experience it in a series of live performances. I hope we can present Transposition in other places in other countries. In the US, in the Arab world, in Europe, wherever it takes us. And Les Arrivants is going very well, we have a few tours coming up. We have a city tour of Montreal coming up, we have a country tour of Colombia coming up in September. I hope Les Arrivants continues to grow and we continue to write the kind of music that we like to play and we like to hear and we like to see people receive.

I do have a project which is with classical guitarist Tariq Harb - we’ve played some pieces by Bach like the two part inventions, we recorded those. We recorded a couple of Turkish classical pieces that I arranged…. Hopefully the recording gets released relatively soon, probably like end of 2026, beginning of 2027. And yeah I just hope that I can continue to do what I’m doing right now and find ways to, you know, sustain my life in all these different artistic projects. Yeah, I mean there’s a lot more left in the tank. We’re just starting.

Well I feel like for the beginning of your full time music career, you’re off to a really good start and I wish you all the best :)

There is so much more to being a musician than just playing music, or even being technically good at what you do. Music requires compassion, experience and a soul to truly make an impact on its audience, and I feel like this is something that shows clearly in Abdul’s discography thus far.

Abdul Wahab-Kayyali has done so much musically in three short years, and despite feeling like a beginner, he displays the reverence of a wise practitioner who’s well accustomed to life as a full time musician. He will surely go on to become one of the greats, pushing for more innovative musical pieces, bringing Arabic classical instruments to modern audiences in a unique way and speaking up against injustices around the world and for the Palestinian people who are currently (and have been) facing unprecedented violence from Israel and the world powers who are arming it.

He will continue to inspire and broaden the horizons of those he comes across, whether that be through his music or his words, for years to come.

I will leave you with the same words Abdul spoke to the audience, before playing the piece Return, the final piece for the night at his Transposition concert:

"Let's hope we all return.”

I wish the best to Abdul on his musical journey and my sympathies for the Palestinian and all oppressed people globally. Let us all hope for a restoration of international laws and justice sooner rather than later.

Instagram: @akayyali

Facebook: @Abboud Kayyali